Drinking Water, Wastewater, and Housing in Vermont

Drinking Water, Wastewater, and Housing in Vermont

What is water and wastewater capacity?

For water systems, capacity refers to the amount of drinking water that is available. This is affected by:

- The amount of water that the source (a well, spring, lake, or river) can provide, which may fluctuate seasonally

- The amount of water that the treatment facility can process

- Water volume and pressure necessary for firefighting

- The amount of water that the distribution system can deliver to homes and businesses in the community

- Age and condition of equipment and infrastructure, including pipes, storage tanks, and pumps

- Regulations on water pressure within distribution pipes

- Staffing levels

For wastewater systems, capacity refers to the amount of wastewater that can be treated. This is affected by:

- The amount of water that the sewer system can transport from homes and businesses to the treatment plant

- The amount of wastewater that the treatment plant can process

- The amount of treated water that the wastewater system is permitted to discharge to the receiving waterbody (a lake or river)

- Age and condition of equipment and infrastructure, including pipes and pumps

- Staffing levels

Capacity is difficult to calculate.

Because so many factors affect capacity, it is difficult to calculate. Water and wastewater systems may not know exactly how much drinking water they can supply or wastewater they can treat.

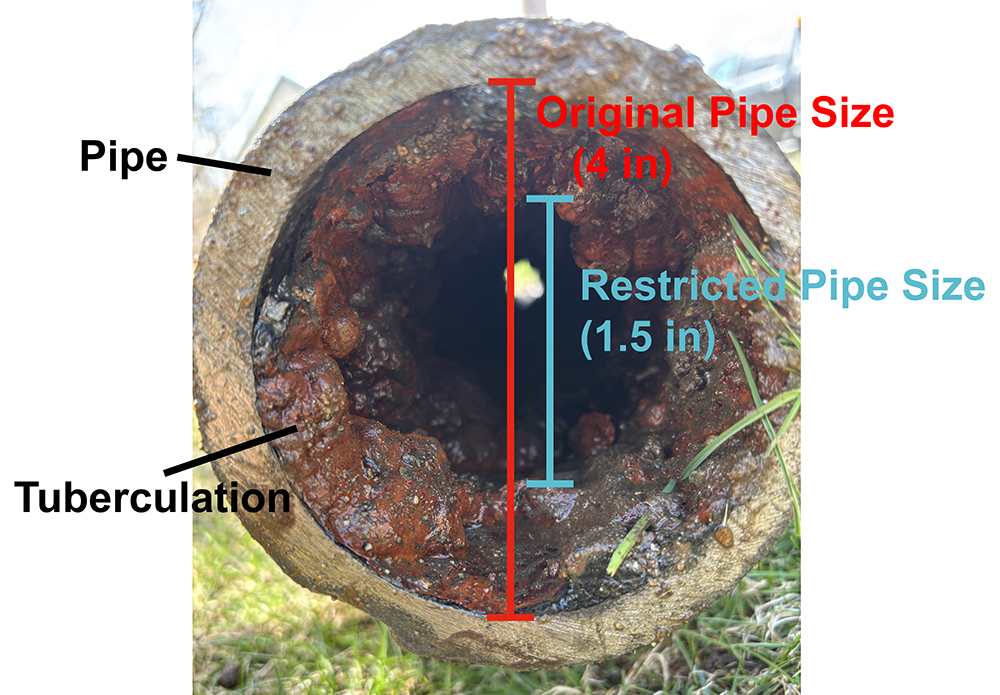

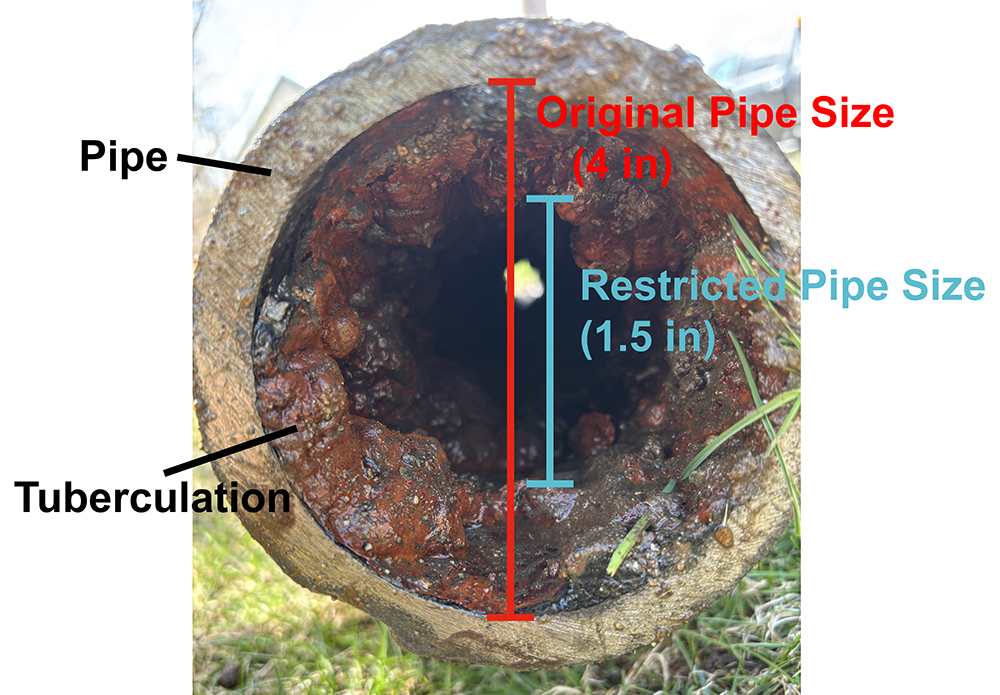

Many of Vermont’s water and wastewater systems were built 50–100+ years ago, and their capacity has decreased as the infrastructure ages.

For example, a water system in southern Vermont recently dug up a water pipe that was installed in 1912. The pipe was 4 inches in diameter, made of cast iron, and was significantly tuberculated (build-up of iron-oxide mounds due to corrosion). This restricted the flow of drinking water down to approximately 1.5 inches, which is an 83% reduction from the pipe’s original flow (480 gallons per minute (GPM) to 80 GPM), plus additional headloss due to friction.

This demonstrates one of the many reasons why systems don’t know their exact capacity—they can’t see what is happening in pipes that are buried underground!

Don't assume there is capacity to support new development.

Just because a community has a public drinking water and/or wastewater system, or a pipe runs down a certain road, doesn’t mean that the water or wastewater system has the capacity to support additional connections, new housing, or new businesses.

Talk to local water and wastewater systems early in the project planning process. A utility’s manager or chief operator has the best understanding of the system’s capacity and limitations, more so than local officials. Talk with the system’s operator early in the planning process about the proposed project’s location and anticipated population. This is the best way to determine if local water and wastewater systems have the capacity to meet the project’s needs. The operator may even be able to suggest upgrades that could improve their system’s capacity, like replacing aging pipes, upgrading pumps, or adding storage tanks.

Utilities track their own allocations, but smaller systems and fire districts may not have an official allocation process. It is difficult to calculate capacity because it is affected by so many factors, so systems may not be able to tell you the exact amount of water they can provide or wastewater they can treat. Systems want to ensure sufficient capacity to serve the needs of all properties under all conditions (think of increased demand for water for firefighting or irrigation).

State agencies do not track capacity or allocations for water and wastewater systems. However, state agencies may need to be involved if increased flow demands require evaluation in order to be compliant with regulations.

Increasing capacity can be expensive.

Unfortunately, increasing capacity at water and wastewater systems is not as simple as withdrawing more water from a source, drilling a new well, or treating more sewage. New permits, new treatment equipment, new distribution/sewer infrastructure, and additional staffing may be needed.

Installing new water and sewer pipes currently costs over $2 million per mile, and the price has increased steeply in the past few years.

Water and wastewater systems also may need additional trained workers if the size of the system increases or more complex treatment methods are added.

In addition, Vermont is experiencing a skilled labor shortage, which makes repair and upgrade projects at water and wastewater systems slower and more expensive. Engineering firms, consulting firms, and construction companies in Vermont are stretched thin. Many recent project bids are coming in significantly over engineering estimates. Smaller projects (less than $1 million) are getting few bids because they are not worth these companies’ time.

While there is state and federal funding available for water and wastewater system upgrades and expansions, the application process is slow and funding is not equally accessible to all water and wastewater systems.

What is water and wastewater capacity?

For water systems, capacity refers to the amount of drinking water that is available. This is affected by:

- The amount of water that the source (a well, spring, lake, or river) can provide, which may fluctuate seasonally

- The amount of water that the treatment facility can process

- Water volume and pressure necessary for firefighting

- The amount of water that the distribution system can deliver to homes and businesses in the community

- Age and condition of equipment and infrastructure, including pipes, storage tanks, and pumps

- Regulations on water pressure within distribution pipes

- Staffing levels

For wastewater systems, capacity refers to the amount of wastewater that can be treated. This is affected by:

- The amount of water that the sewer system can transport from homes and businesses to the treatment plant

- The amount of wastewater that the treatment plant can process

- The amount of treated water that the wastewater system is permitted to discharge to the receiving waterbody (a lake or river)

- Age and condition of equipment and infrastructure, including pipes and pumps

- Staffing levels

Don't assume there is capacity to support new development.

Just because a community has a public drinking water and/or wastewater system, or a pipe runs down a certain road, doesn’t mean that the water or wastewater system has the capacity to support additional connections, new housing, or new businesses.

Talk to local water and wastewater systems early in the project planning process. A utility’s manager or chief operator has the best understanding of the system’s capacity and limitations, more so than local officials. Talk with the system’s operator early in the planning process about the proposed project’s location and anticipated population. This is the best way to determine if local water and wastewater systems have the capacity to meet the project’s needs. The operator may even be able to suggest upgrades that could improve their system’s capacity, like replacing aging pipes, upgrading pumps, or adding storage tanks.

Utilities track their own allocations, but smaller systems and fire districts may not have an official allocation process. It is difficult to calculate capacity because it is affected by so many factors, so systems may not be able to tell you the exact amount of water they can provide or wastewater they can treat. Systems want to ensure sufficient capacity to serve the needs of all properties under all conditions (think of increased demand for water for firefighting or irrigation).

State agencies do not track capacity or allocations for water and wastewater systems. However, state agencies may need to be involved if increased flow demands require evaluation in order to be compliant with regulations.

Capacity is difficult to calculate.

Because so many factors affect capacity, it is difficult to calculate. Water and wastewater systems may not know exactly how much drinking water they can supply or wastewater they can treat.

Many of Vermont’s water and wastewater systems were built 50–100+ years ago, and their capacity has decreased as the infrastructure ages.

For example, a water system in southern Vermont recently dug up a water pipe that was installed in 1912. The pipe was 4 inches in diameter, made of cast iron, and was significantly tuberculated (build-up of iron-oxide mounds due to corrosion). This restricted the flow of drinking water down to approximately 1.5 inches, which is an 83% reduction from the pipe’s original flow (480 gallons per minute (GPM) to 80 GPM), plus additional headloss due to friction.

This demonstrates one of the many reasons why systems don’t know their exact capacity—they can’t see what is happening in pipes that are buried underground!

Increasing capacity can be expensive.

Unfortunately, increasing capacity at water and wastewater systems is not as simple as withdrawing more water from a source, drilling a new well, or treating more sewage. New permits, new treatment equipment, new distribution/sewer infrastructure, and additional staffing may be needed.

Installing new water and sewer pipes currently costs over $2 million per mile, and the price has increased steeply in the past few years.

Water and wastewater systems also may need additional trained workers if the size of the system increases or more complex treatment methods are added.

In addition, Vermont is experiencing a skilled labor shortage, which makes repair and upgrade projects at water and wastewater systems slower and more expensive. Engineering firms, consulting firms, and construction companies in Vermont are stretched thin. Many recent project bids are coming in significantly over engineering estimates. Smaller projects (less than $1 million) are getting few bids because they are not worth these companies’ time.

While there is state and federal funding available for water and wastewater system upgrades and expansions, the application process is slow and funding is not equally accessible to all water and wastewater systems.

Example: Hinesburg

For almost a decade, Hinesburg had various levels of construction moratoriums due to lack of capacity at the municipal water system. Hinesburg’s zoning regulations don’t allow projects to advance until they receive water and sewer allocations. The town had to stall several large developments that would have created over 400 residential units between 2015 to 2020. The town’s two wells were not producing as much water as they once did and also had minor contamination concerns.

Hinesburg’s director of planning and zoning told Seven Days that in a small town with a limited number of customers, it can be too expensive to expand or upgrade infrastructure—the increase in each customer’s bill would be unaffordable. While developers do pay fees to connect to the water system, it’s still difficult to come up with equitable formulas to expand capacity and extend lines while keeping water rates affordable.

To address the lack of water capacity, Hinesburg drilled a new well that provided more drinking water. The town also installed a state-of-the-art nanofiltration system to remove contaminants.

Click to enlarge photos.

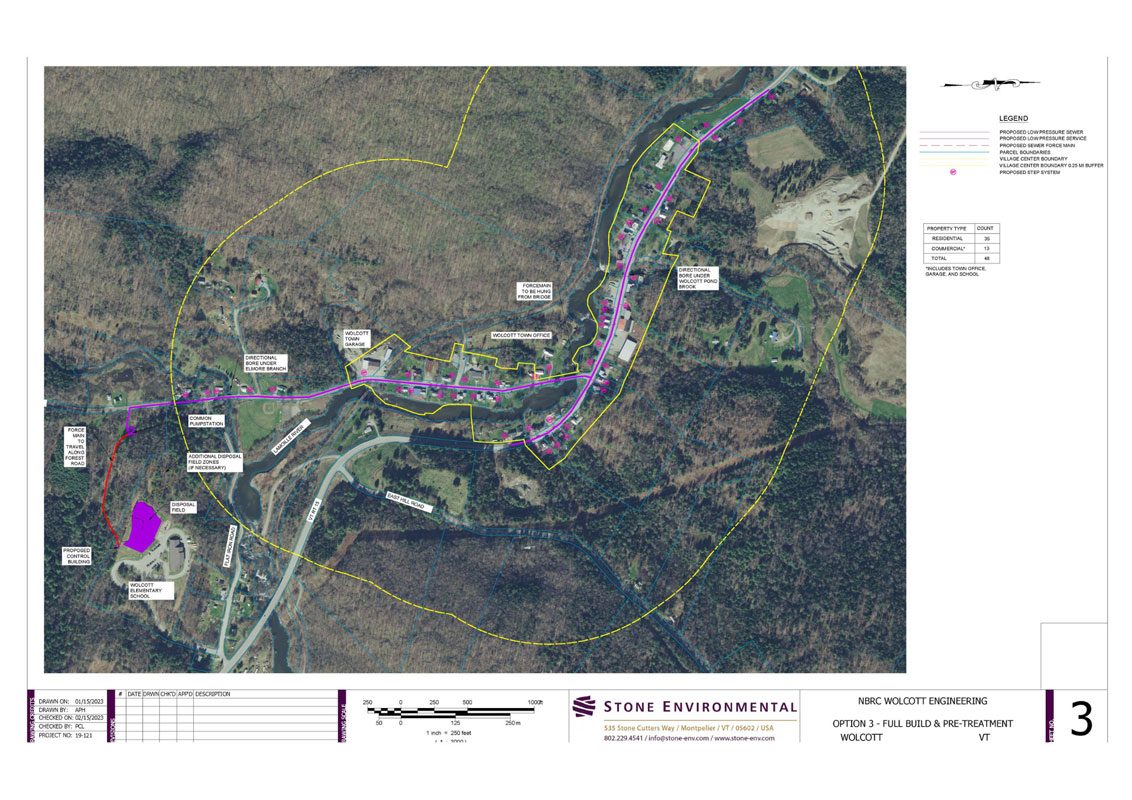

Example: Wolcott

The town of Wolcott doesn’t have a municipal wastewater system, so every building must have its own septic tank to collect wastewater.

Septic tanks are expensive to install and maintain. Individual homeowners and businesses are responsible for the cost of routine pumping and face a hefty price tag if their septic system fails. Individual septic systems also don’t have much capacity, so they may not be able to handle the amount of wastewater generated by apartments or restaurants.

The Wolcott Country Store can’t put in seating because the septic system doesn’t have the capacity to support this. A proposal to turn an old church into an apartment building couldn’t move forward because there isn’t wastewater capacity. (Read more from VTDigger.)

Wolcott Village is currently in the process of installing a decentralized wastewater system to address this problem. The project is being largely funded by ARPA, DEC, and other grants. When it is completed, the new wastewater system is expected to support new businesses and job opportunities, increase property values, and improve water quality in the Lamoille River, according to the Wolcott Wastewater Committee.

Click to enlarge photos.

Hook-up fees may not cover the true cost.

It is generally assumed that increasing a water or wastewater system’s customer base through new connections is financially beneficial to the system, but this may not be the case. Developers do often pay “hook-up fees” to connect a new building or development to a water or wastewater system, and new residents or businesses in the development become paying utility customers. However, this new income may not be enough to offset the cost of expanding the system or increasing capacity. Instead, the price of expansion is paid by all customers (new and existing) through increased water and sewer rates over many years.

Water and wastewater is a community investment.

In rural towns, the community water system and municipal wastewater systems may only serve homes and businesses in the downtown or village core area. Homes in less densely populated parts of town may get their drinking water from a private well and have a septic tank.

But community water systems and municipal wastewater systems benefit all residents, not just those whose homes are connected to them. Important community assets like schools, general stores, town offices, libraries, fire stations, and senior centers often rely on public water and wastewater systems. Because everyone benefits from these institutions, everyone benefits from public water and wastewater systems.

Maps may be inaccurate or nonexistent.

Most water and wastewater systems do not have up-to-date and accurate maps of their water distribution/sewer service areas. Many water systems are more than 100 years old and were not mapped when they were orginally constructed. There have likely been many additions, repairs, and replacements over the years, but these changes may not have been recorded. So while it may be known that there is a water or sewer pipe on a certain road, it may not be known exactly where that pipe is, where valves and connections are, how deep the pipe is, what it is made of, and what condition it is in.

The University of Vermont has been working on a GIS database of sewer systems and may do the same for drinking water distribution systems. But the maps will only be as accurate as the data used to make them—and in many places, that data may not be very accurate.

In addition, all properties within a water or wastewater system’s service area may not be connected to the system. This can happen if older properties already had a private well or septic tank before the system was established, if a system’s bylaws don’t require all new developments to be connected to the system, or if the system didn’t have the capacity to serve a new development when it was built.

Unique challenges in Vermont.

Vermont’s small population, geography, and rural communities create unique challenges for water and wastewater systems. These include:

- Economy of scale. Many of Vermont’s water and wastewater systems serve a small population (the median-sized fire district is 212 customers). Small systems have a higher per capita operating cost, which can lead to higher rates or cut into the system’s savings for emergencies or upgrades. A Vermont Drinking Water and Groundwater Protection Division (DWGPD) employee calculated that a new community water system would need to serve at least 2,000 people to be financially viable.

- Geography. In other places, small towns might collaborate to provide water and wastewater services. In Vermont, where town centers are often far apart and the landscape is hilly, it may not be feasible to consolidate water or wastewater systems.

- Skilled labor shortage. Vermont is experiencing a skilled labor shortage including water and wastewater operators, engineers, consultants, construction companies, and well drillers.

- Opposition to growth. Vermonters value small, rural communities. In some recent cases, residents have opposed water or wastewater projects as a way to prevent growth or development in their town.

- FEMA buyouts. After the floods in 2023 and 2024, some towns considered or approved buyouts of flood-prone properties. For a small water system like Coventry Fire District #1, losing even 5 customers to buyouts would significantly impact their budget.

Hook-up fees may not cover the true cost.

It is generally assumed that increasing a water or wastewater system’s customer base through new connections is financially beneficial to the system, but this may not be the case. Developers do often pay “hook-up fees” to connect a new building or development to a water or wastewater system, and new residents or businesses in the development become paying utility customers. However, this new income may not be enough to offset the cost of expanding the system or increasing capacity. Instead, the price of expansion is paid by all customers (new and existing) through increased water and sewer rates over many years.

Maps may be inaccurate or nonexistent.

Most water and wastewater systems do not have up-to-date and accurate maps of their water distribution/sewer service areas. Many water systems are more than 100 years old and were not mapped when they were orginally constructed. There have likely been many additions, repairs, and replacements over the years, but these changes may not have been recorded. So while it may be known that there is a water or sewer pipe on a certain road, it may not be known exactly where that pipe is, where valves and connections are, how deep the pipe is, what it is made of, and what condition it is in.

The University of Vermont has been working on a GIS database of sewer systems and may do the same for drinking water distribution systems. But the maps will only be as accurate as the data used to make them—and in many places, that data may not be very accurate.

In addition, all properties within a water or wastewater system’s service area may not be connected to the system. This can happen if older properties already had a private well or septic tank before the system was established, if a system’s bylaws don’t require all new developments to be connected to the system, or if the system didn’t have the capacity to serve a new development when it was built.

Water and wastewater is a community investment.

In rural towns, the community water system and municipal wastewater systems may only serve homes and businesses in the downtown or village core area. Homes in less densely populated parts of town may get their drinking water from a private well and have a septic tank.

But community water systems and municipal wastewater systems benefit all residents, not just those whose homes are connected to them. Important community assets like schools, general stores, town offices, libraries, fire stations, and senior centers often rely on public water and wastewater systems. Because everyone benefits from these institutions, everyone benefits from public water and wastewater systems.

Unique challenges in Vermont.

Vermont’s small population, geography, and rural communities create unique challenges for water and wastewater systems. These include:

- Economy of scale. Many of Vermont’s water and wastewater systems serve a small population (the median-sized fire district is 212 customers). Small systems have a higher per capita operating cost, which can lead to higher rates or cut into the system’s savings for emergencies or upgrades. A Vermont Drinking Water and Groundwater Protection Division (DWGPD) employee calculated that a new community water system would need to serve at least 2,000 people to be financially viable.

- Geography. In other places, small towns might collaborate to provide water and wastewater services. In Vermont, where town centers are often far apart and the landscape is hilly, it may not be feasible to consolidate water or wastewater systems.

- Skilled labor shortage. Vermont is experiencing a skilled labor shortage including water and wastewater operators, engineers, consultants, construction companies, and well drillers.

- Opposition to growth. Vermonters value small, rural communities. In some cases, residents will oppose water or wastewater projects as a way to prevent growth or development.

- FEMA buyouts. After the floods in 2023 and 2024, some towns considered or approved buyouts of flood-prone properties. For a small water system like Coventry Fire District #1, losing even 5 customers to buyouts would significantly impact their budget.

Action Items

Invite water and wastewater systems to the table.

Water and wastewater systems are often left out of conversations regarding housing, economic development, emergency response, and hazard mitigation even though drinking water and wastewater infrastructure and capacity are central to community development and planning. Invite operators and managers to provide input at the state and local levels and to weigh in on projects early in the planning process.

When local or state officials consider bills or programs to build new housing, also discuss the need for upgrading local water and wastewater treatment capacity. Talk to the water/wastewater system’s chief operator about what type of upgrades would be needed in order to serve new developments. Don’t just invest in housing—also invest in water and wastewater!

Tour your local water and wastewater systems.

Water and wastewater systems are usually the most expensive infrastructure that towns own. It is important for state legislators, local elected officials, and town managers to be familiar with these vital community assets and aware of the challenges that their local facilities face.

Touring a water or wastewater facility may sound gross or boring, but we promise that the technology and the science that happens on a daily basis will be fascinating, and the operators who work at treatment plants are truly dedicated to serving their communities. (And yes, a wastewater facility can be dirty and smelly. Please dress appropriately.)

Click here to download a list of questions to ask local water and wastewater systems.

Contact your local drinking water and wastewater treatment facilities, they will be thrilled to show you around!

Background Information

What is a water system?

Water system is short for “public drinking water system.” It may be publicly or privately owned. Water system refers to both the water treatment plant and water distribution infrastructure (the underground pipes that deliver treated drinking water to the community).

A community water system has at least 15 connections or serves a residential population of at least 25 people. There are 402 public community water systems in Vermont. Approximately 63% of Vermont’s population receives their drinking water from a community water system. (The rest get their water from private wells and springs.)

There are also several other categories of water systems including non-transient non-community (schools, hospitals, industrial parks, etc.) and transient non-community (restaurants, hotels, campgrounds, churches, etc.).

Click to enlarge photos.

What is a wastewater system?

Wastewater system refers to both the wastewater treatment plant and the sewer collection infrastructure (the underground pipes that carry sewage from homes and businesses to the treatment plant).

There are 92 municipal direct discharge wastewater systems in Vermont. These are owned by towns, cities, villages, and fire districts. Approximately 45% of Vermont’s population is connected to a wastewater system, while the remainder have private septic systems.

There are also several other categories of wastewater systems including indirect discharge, decentralized, and pretreatment facilities.

Click to enlarge photos.

Water System Ownership

Less than one quarter of all community water systems in Vermont are owned by a town, village, or city. Over three-quarters are owned and governed outside of a traditional town municipal structure. “Public drinking water system” DOES NOT always mean publicly owned.

The majority of community water systems are managed by volunteer boards or business owners. They are often operated by a contractor who may not be at the system on a daily (or even weekly) basis. These are typically not organizations with the capacity to apply for grants or plan for future infrastructure needs.

| Type of Owner | Number of Water Systems | Percent of Water Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Town, City, Village | 91 | 22% |

| Water District | 8 | 2% |

| Fire District | 71 | 17% |

| MHP, HOA, Condo Assoc., Housing Nonprofit, or Co-Op | 190 | 47% |

| Corporation or Other Private Entity | 43 | 11% |

| Total – Community Water Systems | 403 |

Water System Ownership

Less than one quarter of all community water systems in Vermont are owned by a town, village, or city. Over three-quarters are owned and governed outside of a traditional town municipal structure. “Public drinking water system” DOES NOT always mean publicly owned.

The majority of community water systems are managed by volunteer boards or business owners. They are often operated by a contractor who may not be at the system on a daily (or even weekly) basis. These are typically not organizations with the capacity to apply for grants or plan for future infrastructure needs.

| Type of Owner | Number of Water Systems | Percent of Water Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Town, City, Village | 91 | 22% |

| Water District | 8 | 2% |

| Fire District | 71 | 17% |

| MHP, HOA, Condo Assoc., Housing Nonprofit, or Co-Op | 190 | 47% |

| Corporation or Other Private Entity | 43 | 11% |

| Total – Community Water Systems | 403 |

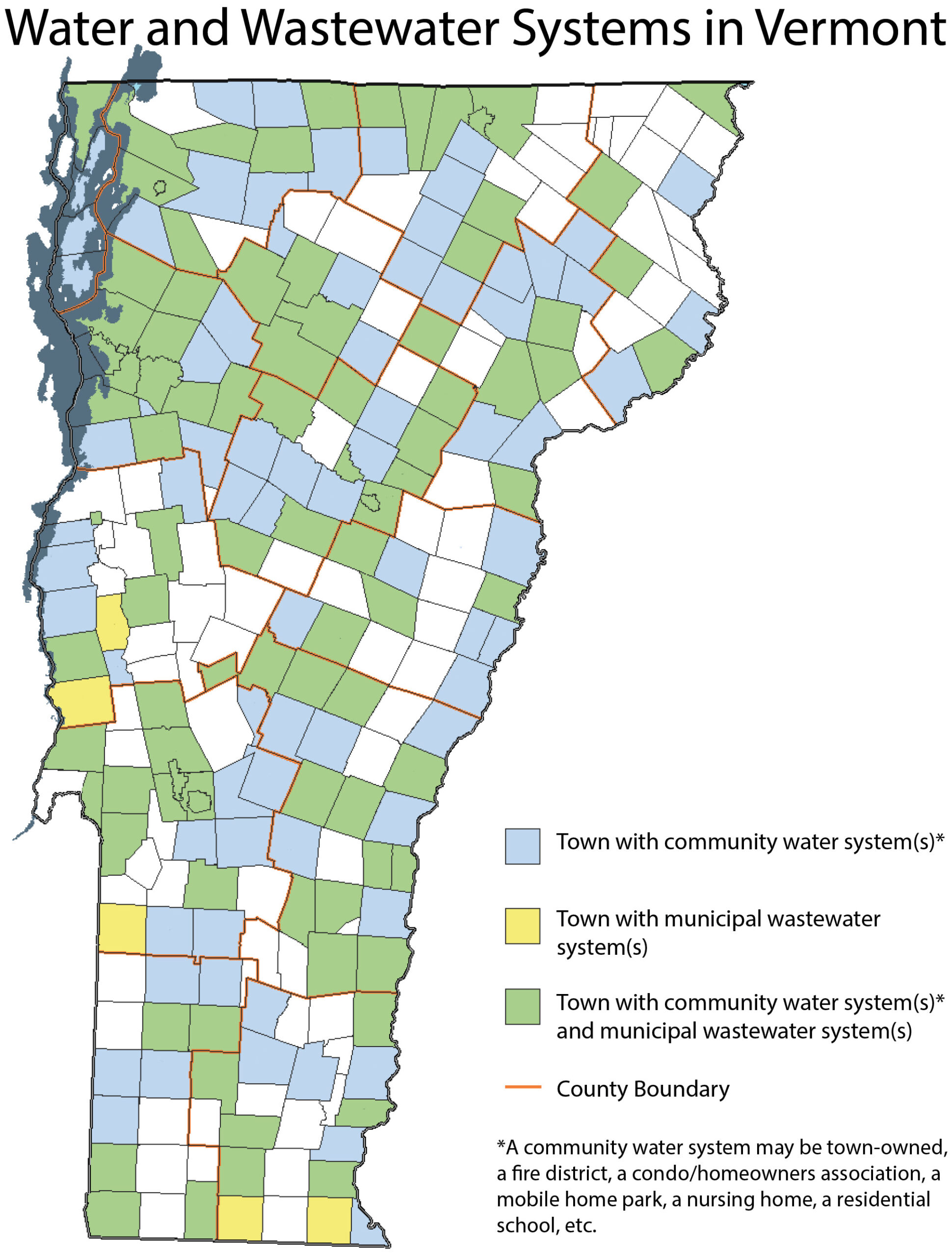

Map of Towns with Water and Wastewater Systems

Map of towns with community or NTNC water systems and/or municipal wastewater systems. Click to view a larger image.

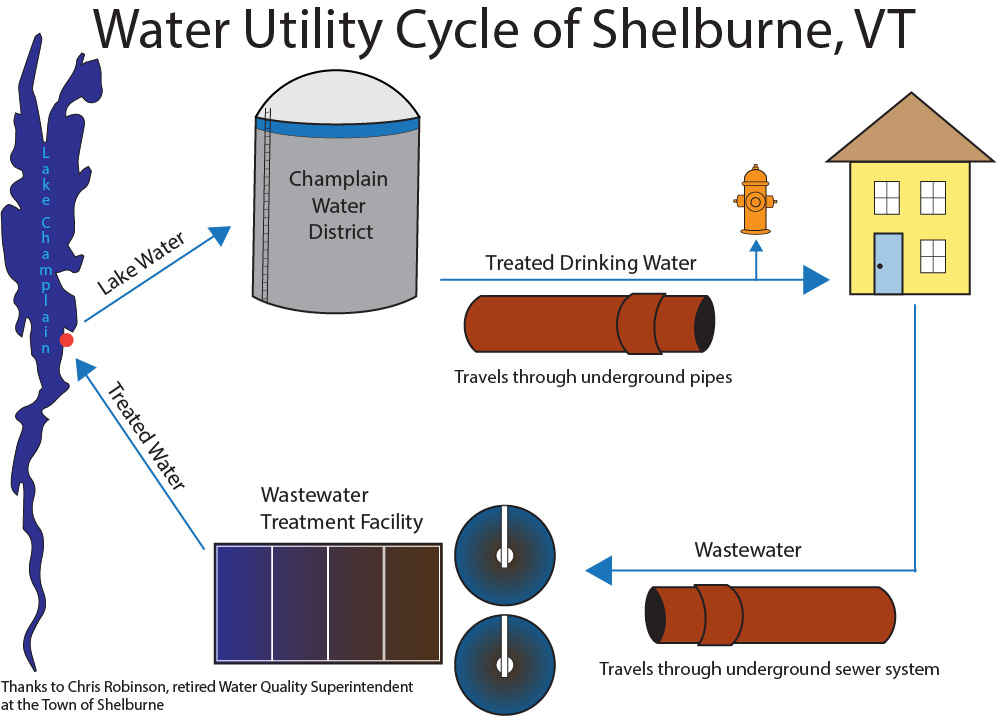

Diagram of a Water and Wastewater System

The Town of Shelburne’s water travels through these steps:

- Water is pumped from Lake Champlain to the Champlain Water District facility for treatment.

- Treated drinking water is delivered to homes and businesses through an underground network of distribution pipes.

- Water is used in homes and businesses and becomes wastewater.

- Wastewater travels through an underground network of sewer pipes to the wastewater treatment facility.

- The wastewater undergoes a series of treatment methods to remove pathogens, nutrients, and other contaminants.

- Treated water is returned to Lake Champlain. (Note that in most communities, drinking water does not come from the same water source that treated wastewater is returned to.)

Customer Bill Assistance

During the Covid pandemic, several state and federal assistance programs helped customers pay their water and sewer bills. The programs were phased out as the pandemic ended, but there is still need for this funding. Vermonters continue to call asking for help paying their water bills, even though these assistance programs ended years ago.

Residents with private wells and septic systems also ask for funding or technical assistance to fix or replace their well or septic tank. This need is heightened during times of drought and flooding.

Role of the Public Utilities Commission (PUC)

The Vermont Public Utility Commission only has 17 water companies under its jurisdiction, including several ski resorts, water corporations, and housing developments. Not all of those are even public water systems. The Vermont PUC does not oversee 97% of public community water systems and does not regulate any wastewater systems. Therefore, having programs intended to assist water or wastewater systems run through the PUC does not make sense.

Example: Jeffersonville

Since 2018, there has been a moratorium on new connections to the Village of Jeffersonville water system. The moratorium was placed by the Vermont Drinking Water and Groundwater Protection Division (DWGPD) because of concerns that Jeffersonville’s water source couldn’t provide enough water. New construction projects have had to either provide their own drinking water through a private well or be put on hold.

The Village drilled two new wells, but one didn’t yield enough water and the other was contaminated with PFAS.

The water operator has spent several years finding and fixing leaks in the system’s aging pipes, which has saved a tremendous amount of water. A village trustee estimated that they were previously losing about half of their water to leaks, according to an article in News & Citizen.

Read more from News & Citizen here.

Example: Killington

Several years ago, PFAS contamination was found at several small public water systems along Killington Road. PFAS is a class of “forever chemicals” that have been linked to cancer and other health effects.

In 2022, the Town of Killington assumed the responsibility of creating a municipal water system that will provide safe and reliable drinking water to homes and businesses that had PFAS contamination in their wells, and allow other businesses and private residents to connect. The water system is projecting 770 service connections to begin with, and more will be added in time.

The new water system will have fire hydrants, something Killington hasn’t had before, so improved fire protection is an added benefit of the project.

Construction began on the new water system this summer. The town has drilled three wells that will be the water sources. Sampling found no detections of PFAS in the new wells.

The wells have a capacity of 1.8 million gallons per day (MGD). The water will be pumped to two storage tanks on Shagback Mountain, which will gravity feed the water system.

The first service connection is expected in the spring of 2026. The remaining portion of the water system will be contracted out to finish water lines and service connections.

The total cost of the project is estimated at $43 million, with $32 million for construction costs. It is funded through a combination of sources, including tax increment financing (TIF), funding from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), State Revolving Fund (SRF) loans, a Catalyst Program grant from the Northern Borders Regional Commission, and USDA Rural Development financing.

The water system is a major component of the “Killington Forward” initiative. The new water system will allow for growth and economic development, including new workforce housing and commercial properties. The water system will also provide drinking water for the proposed Six Peaks Ski Village that has been in the planning process for the last 30 years.

Example: Jeffersonville

Since 2018, there has been a moratorium on new connections to the Village of Jeffersonville water system. The moratorium was placed by the Vermont Drinking Water and Groundwater Protection Division (DWGPD) because of concerns that Jeffersonville’s water source couldn’t provide enough water. New construction projects have had to either provide their own drinking water through a private well or be put on hold.

The Village drilled two new wells, but one didn’t yield enough water and the other was contaminated with PFAS.

The water operator has spent several years finding and fixing leaks in the system’s aging pipes, which has saved a tremendous amount of water. A village trustee estimated that they were previously losing about half of their water to leaks, according to an article in News & Citizen.

Read more from News & Citizen here.

Click to enlarge photos.

Example: Killington

Several years ago, PFAS contamination was found at several small public water systems along Killington Road. PFAS is a class of “forever chemicals” that have been linked to cancer and other health effects.

In 2022, the Town of Killington assumed the responsibility of creating a municipal water system that will provide safe and reliable drinking water to homes and businesses that had PFAS contamination in their wells, and allow other businesses and private residents to connect. The water system is projecting 770 service connections to begin with, and more will be added in time.

The new water system will have fire hydrants, something Killington hasn’t had before, so improved fire protection is an added benefit of the project.

Construction began on the new water system this summer. The town has drilled three wells that will be the water sources. Sampling found no detections of PFAS in the new wells.

The wells have a capacity of 1.8 million gallons per day (MGD). The water will be pumped to two storage tanks on Shagback Mountain, which will gravity feed the water system.

The first service connection is expected in the spring of 2026. The remaining portion of the water system will be contracted out to finish water lines and service connections.

The total cost of the project is estimated at $43 million, with $32 million for construction costs. It is funded through a combination of sources, including tax increment financing (TIF), funding from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), State Revolving Fund (SRF) loans, a Catalyst Program grant from the Northern Borders Regional Commission, and USDA Rural Development financing.

The water system is a major component of the “Killington Forward” initiative. The new water system will allow for growth and economic development, including new workforce housing and commercial properties. The water system will also provide drinking water for the proposed Six Peaks Ski Village that has been in the planning process for the last 30 years.

Click to enlarge photos.