by Tim Russo

This article was published in the winter 2023-2024 issue of our newsletter.

If your drinking water source is a drilled bedrock well, it probably doesn’t require a great deal of attention from an operation and maintenance perspective. Here in Vermont, we are blessed with many clean and productive drilled bedrock wells.

But after this summer’s excess rainfall and flooding, many wells have tested positive for total coliform bacteria (or worse). Vermont Rural Water has a nano down-well camera that Brad Roy, our source water specialist, and I have been using to help drinking water systems investigate bacterial contamination.

Tim Russo inspects a well using a specialized camera.

The camera is a slender, submersible unit, with the lens pointed down (unfortunately, no side views!) and a light to provide illumination. The camera is connected to a spool of wire, several hundred feet in length. On that spool is a meter which tells the current camera depth.

The wire spool is connected to a console that displays real-time video from the camera. We often connect a television screen so everyone can easily see the video. We also record the video so it can be reviewed later, and the camera depth is encoded in the video. Afterwards, we will give you a copy of the recording, as well as a one-page summary report. You can share with your well driller if the investigation finds that the well needs maintenance.

As the camera is lowered into the well, we can check the condition of the pitless adapter, the static water level, and the well casing’s condition and length. When we pass from casing into the bedrock, things start to get interesting.

What we are generally looking for, at this point in the inspection, is whether there are any fractures in the bedrock just below the casing that are allowing water to infiltrate the well. Aquifers naturally filter groundwater by forcing it to pass through small pores and between sediments, which helps to remove contaminants. However, fractures close to the surface may allow water to enter the well that hasn’t yet had time to be adequately filtered.

Camera view of a well’s casing.

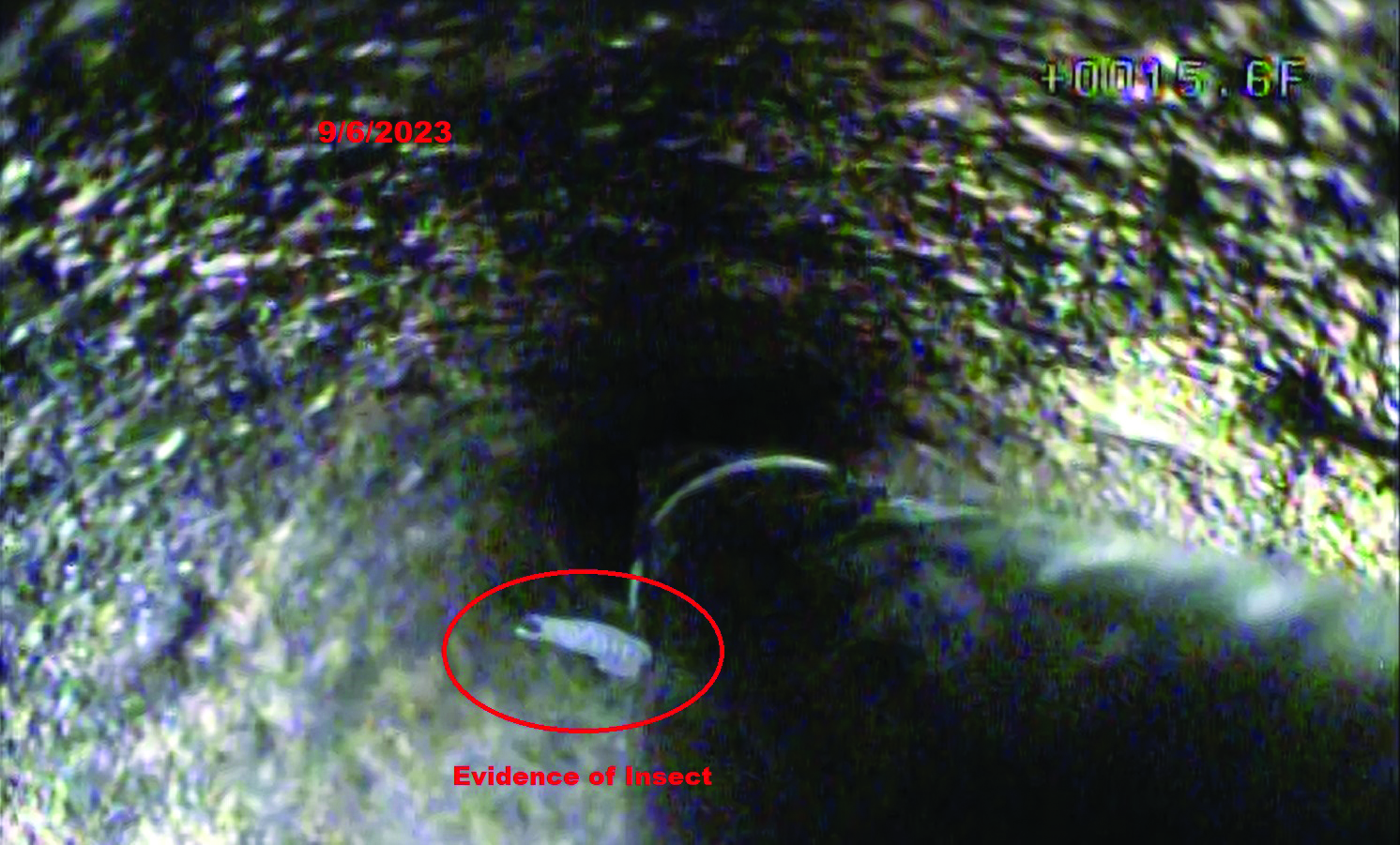

Evidence of an insect inside a well (circled in red)

With the rainy conditions we had this summer, and the resulting high water table, we’ve seen many wells where inadequate casing is the likely cause of bacteria hits. What to do about it? Ask your well driller for options. They may suggest a casing extension, or Jaswell Seal (also called a well packer).

It could also be that as the water table returns to normal levels, total coliform issues will resolve on their own. But as we have witnessed with climate change-related extreme weather events, it’s just a matter of time before you experience issues again.

In addition to total coliform hits, we’ve also used the camera to investigate wells that have high turbidity or have tested positive for PFAS contamination.

Some things to consider before doing a well camera investigation include that the pump will not be able to run during the inspection and the well will need to be shock chlorinated afterwards. Water system personnel will be responsible for removing the well cap/seal and disconnecting electrical power to the well. Any time the well cap is removed, there is a risk of contamination. We strongly advise that after the camera inspection is complete, you shock chlorinate the well to mitigate the risk of contamination. You are also responsible for reinstalling the cap/seal and putting the well back into service.

As a reminder, there is no charge for a well camera investigation from Vermont Rural Water, or for any of our technical assistance services, so don’t hesitate to reach out if you have questions or need help.